I Can’t See Inside Their Head

A mantra to stick to what you know is true in hard conversations

Last week in The Idea Bucket we pivoted from preparing for negotiations in career conversations to talking about the power of language choice when navigating conflict. Today we continue the leadership theme of having hard conversations.

We've already talked about how regular feedback is one of the keys to building a subculture of innovation. And I've given you both one-on-one and team rituals to practice this regularly.

Today I want to focus on a fundamental framework for having hard conversations that, once you begin using it, will have an impact on both your professional and personal relationships.

It's a mantra to say to yourself when you are having a hard conversation: I Can’t See Inside Their Head

It helps you stick to what you know is true and avoid making statements that might start a cycle of misunderstanding and defensiveness.

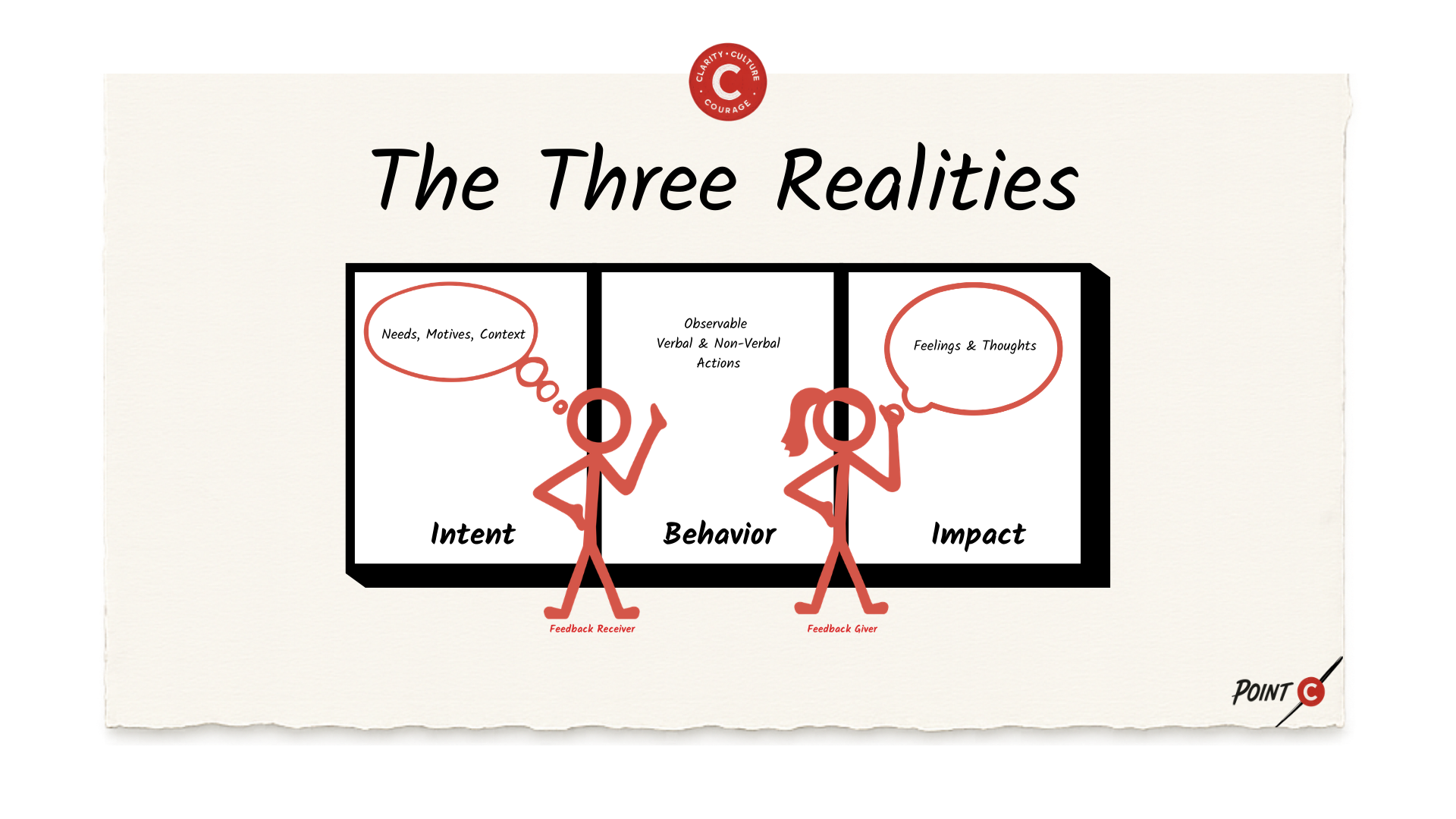

The Three Realities

As with most of my work involving feedback and disclosure, these lessons come straight from my mentor, Carol Robin. I highly recommend that you buy her book Connect, which is required reading for my Sulzberger fellows. She also runs a great program called Leaders in Tech if you want to immerse yourself in these principles.

As Carole teaches, every feedback interaction between two people has three realities:

1) The Shared Reality - This is the observable behavior between the two people - the feedback giver and the feedback receiver. This includes actions as well as verbal and non-verbal behavior.

For example, imagine you are a CEO presenting a new growth strategy in your executive meeting. Halfway through, your CFO says, “I’m not sure these revenue assumptions are realistic.”

Both of you can observe that the CFO publicly questioned the assumptions in the meeting. That is observable and true for both people.

2) The Inner World of The Feedback Giver - These are the thoughts and feelings of the person who has been impacted by the behavior.

In this case, you might feel embarrassed, undermined, or frustrated. You might start telling yourself a story that they don’t believe in the strategy or that they’re trying to make you look bad in front of the team.

While the CFO might guess how you feel, they don’t actually know. Those thoughts and feelings are only known to you unless you disclose them.

3) The Inner World of The Feedback Receiver - These are the needs, motives, and context of the person who performed the behavior in question. It's their intent.

Perhaps the CFO is worried about cash runway. Perhaps they thought raising the concern publicly would strengthen the plan. Perhaps they thought this was a way they could actually have your back before you took this plan public.

That context is only known to them unless they disclose it.

Overall, in the absence of disclosure, we only know two of the three realities. You know the shared reality and your own inner world. They know the shared reality and their own inner world.

Neither of you knows the other’s inner world. The problem occurs when you think you do.

The Trap of The Third Reality

Pretty simple, right? Why is this concept so important? Because when we give people feedback, we often make the critical mistake of thinking we can see inside the other person’s head. We believe we know their inner world. We believe we can confidently state what was going on inside of them.

After that executive meeting, you could say:

“You clearly don’t believe in this strategy. You're trying to undermine me in front of the team.”

It happens all the time. But it's a mistake.

It’s possible they don’t believe in the strategy. But without disclosure of intent, you don’t actually know that.

And if you’re wrong, it starts a vicious cycle where the other person feels deeply misunderstood.

We’ve all experienced this. Someone makes a declarative statement about us that only we could know and that we know is not true. We feel misunderstood, frustrated, and unseen. We try to make a correction but then we’re accused of being defensive, not listening, or making excuses.

We’re faced with a choice of continuing to argue the point, distracting from the bigger conversation and deepening their perception that we are defensive, or withdrawing, giving up on the hope that this person truly wants to understand us.

Either way, we aren’t getting closer to understanding.

Stick To Your Two Realities

In that meeting, you had a different choice.

Instead of pretending that you could see inside your CFO’s head, you could have owned your two realities. You could have said:

“When you questioned the revenue assumptions in the meeting, I felt caught off guard and a bit undermined. Can you tell me what was driving that?”

What you’re saying here is true. You know what happened, and you know how it made you feel.

You also move toward inquiry. You’ve disclosed information they couldn’t see, and you’ve opened space for them to disclose their inner world.

Carole Robin would call this technique “staying on your side of the net.” She’d ask you to imagine a playing court where there is a net separating you from that third reality. You can confidently play on the side of the court that occupies your two realities. But don’t jump over the net and try to play in the inner world of your counterpart.

"When You Did X, I Felt Y"

Fortunately there is a magic phrase that can keep you from pretending that you can see inside the other person's head:

"When you did X, I felt Y"

In this case:

“When you questioned the revenue assumptions in the meeting, I felt embarrassed and caught off guard.”

This simple grammatical rule ensures that you only say what you know to be true: 1) You know the observable behavior and 2) you know your inner world of feelings and thoughts.

Now, people find a way to break this rule as well. They do it by simply adding "that you" to the sentence:

"When you did X, I felt that you..."

“When you questioned the revenue assumptions, I felt that you don’t believe in this strategy.”

That’s not a feeling word. It’s a judgment disguised as one. It’s just another way to pretend you know what is going on in the other person’s head.

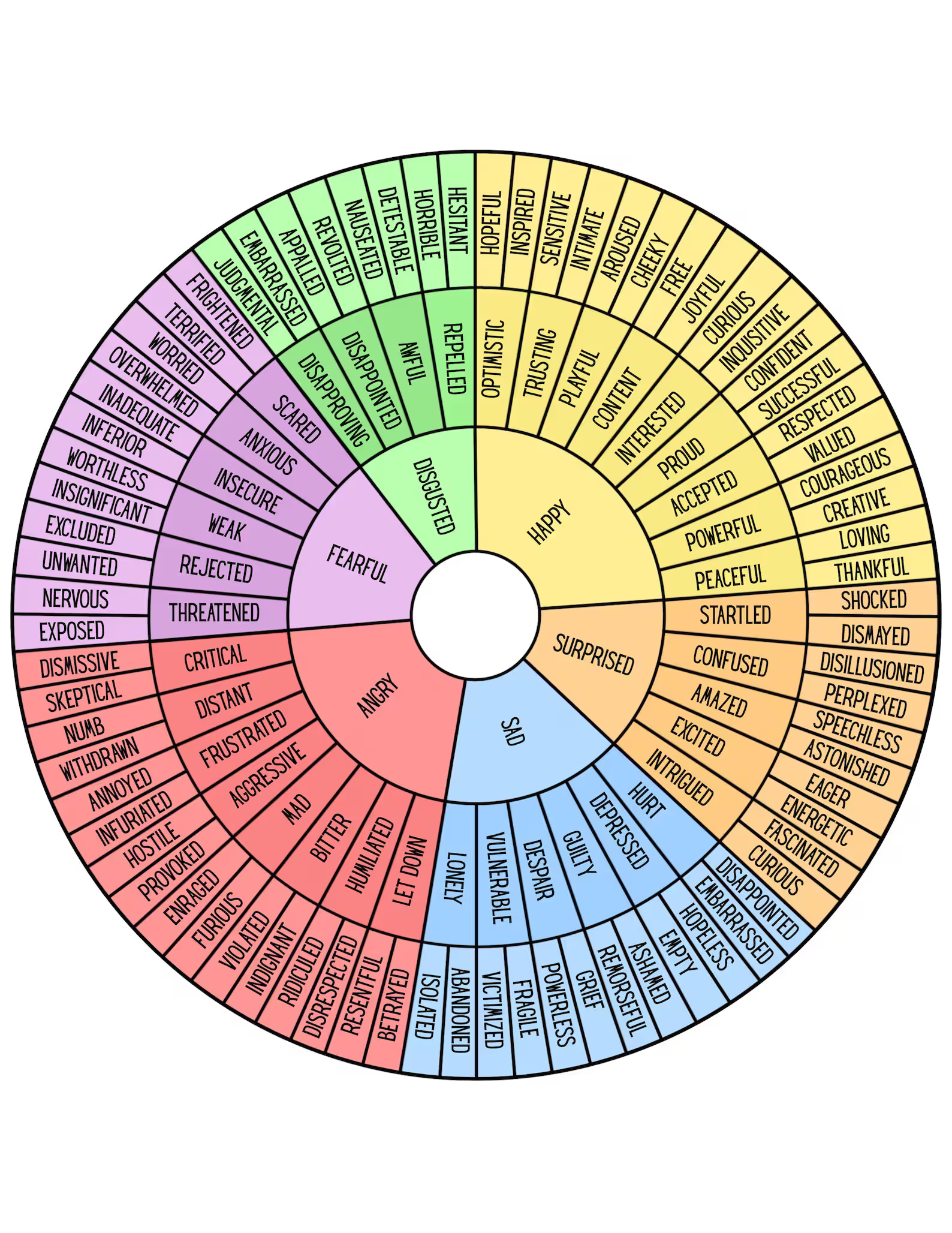

So the key rule here is that Y in this sentence construct has to be a feeling word. If you need help, look at this chart and find a feeling word:

"The Story I'm Telling Myself..."

Now, I have to admit that sticking to your two realities is not easy, especially during difficult conversations. I teach this principle regularly and even I break this rule more often than I’d like to admit.

So here’s a way to catch yourself:

If you absolutely cannot hold yourself back from pretending that you can see into the other person's head, you can use this phrase:

"...the story that I am telling myself is..."

You could say:

“When you questioned the revenue assumptions, the story I am telling myself is that you don’t believe in the strategy.”

Does this still speculate about intent? It does. But it owns the speculation.

By adding “...the story I’m telling myself...,” you own that this is your perception — and that it may be wrong. It gives just enough room to prevent the spiral of misunderstanding.

"When you did X, I felt Y" is best, but "...the story I'm telling myself..." is a better fallback than confidently pretending that you can see inside their head.

Intent Is Not An Excuse

One important clarification:

I'm not arguing that intent erases responsibility for the impact of a certain behavior. Just because it wasn't your intent, doesn't absolve you of responsibility for the impact of your actions.

This isn't about making excuses. This is about owning your behavior and being able to have a healthy and curious dialogue about what happened so everyone can truly understand the full context.

This Shows Up Everywhere

This dynamic isn’t limited to executive meetings. It shows up across every kind of relationship.

Here are two quick examples.

Between A Manager & Direct Report

A manager notices that a direct report missed an important deadline.

Shared reality:

The deadline passed and the work wasn’t delivered.

The manager’s inner world:

Frustrated. Concerned about reliability. Worried about the impact on the rest of the team.

The employee’s inner world:

Possibly overwhelmed. Unclear on shifting priorities. Maybe dealing with something personal. The manager doesn’t know.

Now the manager has three choices:

1) They can pretend that they can see inside the employee’s head:

“You clearly don’t take deadlines seriously.”

If they do, the employee will likely feel judged. They may defend themselves or withdraw. The conversation shifts from performance to character, and it becomes harder to solve the real issue.

2) They can soften it with:

“When the deadline passed, the story I’m telling myself is that this wasn’t a priority for you.”

That still introduces a story, but owns the fact that it is just a story. The employee has space to clarify. The temperature drops.

3) Or they can pause, say to themselves "I can't see inside their head", and stick to their two realities:

“When the deadline passed, I felt concerned and frustrated. Can you help me understand what happened?”

Now the manager has said only what they know to be true. The employee is more likely to explain context. The conversation moves toward clarity instead of accusation.

In Your Personal Life

You tell your partner that it would mean a lot to you if they called when they landed from a trip. They say they will. They don’t.

Shared reality:

They didn’t call.

Your inner world:

You feel hurt. Maybe unimportant. Possibly even anxious if you were worried about their travel.

Their inner world:

They might have been exhausted. Their phone battery may have died. They may have gotten caught up in baggage claim and simply forgotten. You don’t actually know.

Once again, you have three choices:

1) You can pretend that you can see inside their head and say, “You don’t care about me.”

If you do, the conversation quickly shifts to defending character. They are likely to feel unfairly accused, and now you are arguing about whether they care instead of talking about what actually happened.

2) You can soften it by saying, “When you didn’t call, the story I’m telling myself is that I’m not a priority.”

That still introduces a story, but it makes clear that it is your interpretation. It creates some room for them to respond without immediately defending themselves.

3) Or you can pause, say to yourself "I can't see inside their head", and stick to your two realities: “When you didn’t call, I felt hurt and unimportant. What happened?”

Now you are naming your experience without assigning intent. You have said only what you know to be true. That simple shift makes it much more likely that the conversation leads to understanding instead of escalation.

In every context — executive team, management relationship, or marriage — the pattern is the same.

When you assign intent, the conversation tightens. When you disclose impact and inquire, it opens.

You can’t see inside their head. You can only own your two realities.

Your Challenge This Week

Practice staying in your two realities.

In your next feedback conversation, whether it be with a professional colleague or, dare I say, your partner at home, be intentional about your words. Be mindful of when you are tempted to pretend you can read their minds.

Practice saying "When you did X, I felt Y." moving into inquiry. See what it feels like to say "...the story I'm telling myself is..." Do you notice a shift in the reception?

Also, notice what it feels like to be on the other side of the conversation. When someone says something that pretends they can jump into your inner world, how do you feel? What would have felt better?

That answer is usually the discipline you need to practice.

Next Week

We've begun to master our language in conflict and hard conversations. Knowing these skills are essential to building a subculture of innovation, where as a leader you are striving for both high standards and high psychological safety.

Next week, we'll return to the concept of high psychological safety and we'll explore the specific leadership levers that you can pull to move your culture from the anxiety zone to the learning zone.

About This Newsletter

The Idea Bucket is a weekly newsletter and archive featuring one visual framework, supporting one act of leadership, that brings you one step closer to building a culture of innovation.

It’s written by Corey Ford — executive coach, strategic advisor, and founder of Point C, where he helps founders, CEOs, and executives clarify their visions, lead cultures of innovation, and navigate their next leadership chapters.

Want 1:1 executive coaching on this framework or others? Book your first coaching session. It's on me.